Searching, Replacing and Comparing Files

Searching in Files

The grep command is used for searching files. The basic usage of

grep is to pass the pattern to search for as the first

argument, and the file or files to search in as the second argument. For

example, to search for the text "hello" in files a.txt, b.txt and c.txt:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ grep hello a.txt b.txt c.txt a.txt:hello there c.txt:this line contains hello c.txt:this line contains hello as well

As you can see, grep prints all lines in the input files which

contain the patten searched for. Here, a.txt has one match, b.txt has none,

and c.txt has two.

grep has a number of useful options:

-iIgnore case. With this option, if we search for "hello", it will also match "Hello", "HELLO", "hElLo" etc. The default behavior of

grepis to only match if the case is the same.-vInvert match. With this option,

grepwill list all of the lines that do not contain the text we are searching for.-nPrint line numbers. With this option,

grepwill print the line that each match occurs on.-rWith this option, grep will search recursively. That is, if you pass it a directory name, grep will search for the pattern in any files in that directory.

For example, if we want to find all instances of a function called "getData" inside of project that we are working on, we could use the following command:

ifinlay@cpsc:project1$ grep -inr getData . ./main.py:7: user_data = getData() ./test.py:13: test_data = getData() ./data.py:14:# the getData function gets some data from the user and returns it ./data.py:15:def getData():

This command uses the -i option to ignore case (useful if we can't recall how we capitalized something), the -n option to print line numbers, and the -r option to search any where within the current directory (".")

grep is a very powerful program. The patterns it searches for do

not have to be plain strings, they can be regular expressions. These are

beyond the scope of this course, but allow for very complex searches.

Searching for Files

grep is for searching the contents of files, but cannot search for a file

by name. For that, we need the find command.

find takes as its first argument the starting point for the search. To

search the entire file system, this can be "/". To search your entire home directory,

use "~". To search from the current location, use ".". find always

searches recursively from its starting point.

After that come a number of tests. Likely the most common one is the "-name" test which takes a name to match. For example, we can use the following command to find all files named "main.py" in our home directory:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ find ~ -name main.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/project1/main.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/project2/main.py

The file name we pass can also contain the * and ? wild card characters. So to find all Python files in our home directory, we might use:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ find ~ -name "*.py"

Which will print all files which end in ".py". Note that the "*.py" part is in quotes. That is needed because otherwise, the shell would expand the wildcard to be the files in the current directory that match the pattern. With the quotes, the text "*.py" is passed as is into find which searches recursively for the pattern.

Some other potentially useful tests are summarized below (many more can be

found by consulting man find):

-emptyMatches all empty files.

-executableMatches all files which have the executable permission.

-mmin -NMatches all files which were modified within the last N minutes. Here you replace N with the number of minutes you wish.

-size +NuMatches all files using at least N of u units of file size. For instance,

-size +100kmatches files using at least 100 kilobytes,-size +20Mmatches those using 20 megabytes, and-size +1Gmatches those of at least 1 gigabyte.-type dMatches only directories, not regular files.

-type fMatches only regular files.

Multiple tests can be combined, so to find all executable Python files modified within the last hour we could use:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ find ~ -executable -name "*.py" -mmin -60 /home/faculty/ifinlay/project1/main.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/project1/test.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/bin/get-attachments.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/bin/lookup.py /home/faculty/ifinlay/project2/main.py

One common goal of the find command is to perform some task on the

files we find. For instance, we might want to use the ls -l command

to see file details of some set of files. To do this, we can use the -exec

option of find. After the -exec comes the command we want to

run with the characters "{}" in place of the filename, followed by a "\;".

For instance, the following command applies ls -lh to get file

details on the Python files we found above:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ find ~ -executable -name "*.py" -mmin -60 -exec ls -lh {} \;

-rwxr-xr-x 1 ifinlay faculty 4.4K 2018-07-08 16:12 /home/faculty/ifinlay/bin/get-attachments.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 ifinlay faculty 1.4K 2018-07-08 16:11 /home/faculty/ifinlay/bin/lookup.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 ifinlay faculty 47 2018-07-08 15:48 /home/faculty/ifinlay/project1/main.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 ifinlay faculty 41 2018-07-08 15:49 /home/faculty/ifinlay/project1/test.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 ifinlay faculty 47 2018-07-08 16:11 /home/faculty/ifinlay/project2/main.py

What find does is first find all of the files that matches our criteria. Then it runs

the command after -exec on them, substituting the filename in for the {}.

This feature allows for lots of flexibility. find lets us select some

subset of files using all kinds of criteria, and allows us to run arbitrary commands

on them.

Comparing Files

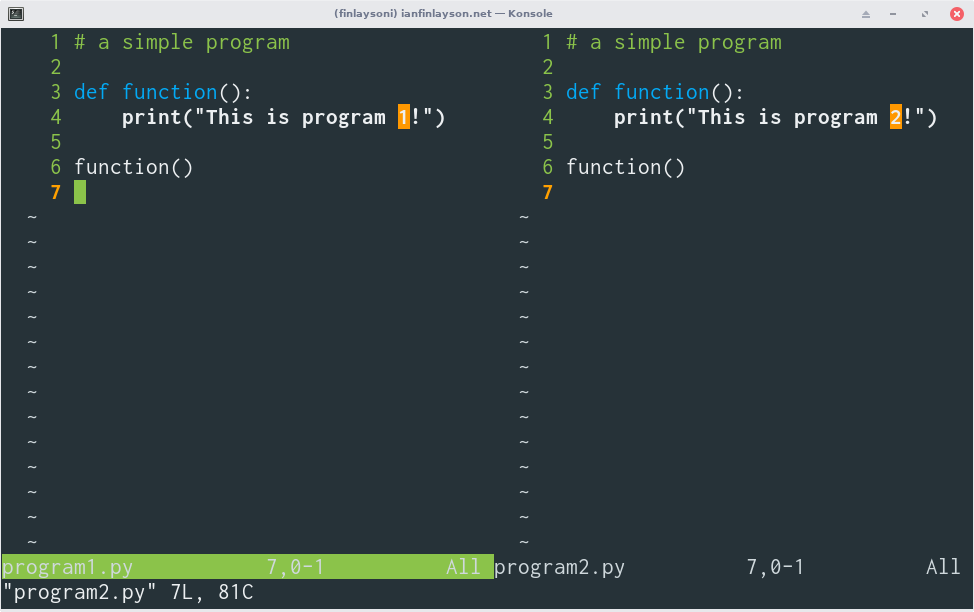

Sometimes we need to compare two files to see what differences are between them. For instance, we may want to compare two versions of a program that we are working on, or compare the output of our program with the correct output to see if it matches.

A simple tool for comparing files is the diff command which prints

the differences in two files. For example, if we have two files "program1.py"

and "program2.py", as shown below:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ cat program1.py

# a simple program

def function():

print("This is program1!")

function()

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ cat program2.py

# a simple program

def function():

print("This is program2!")

# call the function

function()

We can print the differences with diff by passing the

two files as arguments:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ diff program1.py program2.py

4c4

< print("This is program1!")

---

> print("This is program2!")

5a6

> # call the function

The output of diff contains a number of differences.

Each starts with a line with two line numbers separated by a character

indicating the type of difference. Here, 4c4 indicates that on

line 4 of the first file, and line 4 of the second file, there is a change.

Likewise the second difference, 5a6says that line 5 of the first file, there

is a difference which is an added line which would appear at line 6 of the

second file. diff also reports deleted lines with the d

character.

After indicating the type of difference, diff gives the

details. In the first instance, this consists of the lines:

< print("This is program1!")

---

> print("This is program2!")

This shows the differences in the lines, the first file first, and

the second second. For the other difference, diff shows the

line that was added.

The output of diff is not very convenient for humans

to read (though it is used for programs like git). It's

usually easier to see differences visually with sdiff which

is a "side by side" difference viewer.

sdiff also takes two files as arguments, the output

for the two Python programs is shown below:

# a simple program # a simple program

def function(): def function():

print("This is program1!") | print("This is program2!")

> # call the function

function() function()

The output of sdiff shows the two files side by side, with marks in

the center indicating the differences. A '|' character indicates that the line

is different, a '>' indicates a line which is only in the second file, and a

'<' indicates a line which is only in the first.

The last tool we will discuss for looking at differences between files is

vimdiff, which is part of Vim, and provides an interactive way of

browsing differences.

Like the other tools, we pass the files to vimdiff as arguments:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ vimdiff program1.py program2.py

vimdiff opens up Vim with a split window, showing the files

side by side as in the following example:

vimdiff screen

vimdiff allows all of the Vim navigation commands we have learned as well as two

others:

]c- jump to the next change in the files.[c- jump to the previous change in the files.Control-w w- switch between sides. (This command means hold control, tap w, release control and tap w again). Vim actually allows for split windows to show multiple files outside ofvimdiffas well.

vimdiff also allows us to merge the changes from one

file or the other. If we are in the left file, and type dp,

then we put this line into the other file. If we type do,

then we get the other file's line and place it in the current one.

For example, if we were on line 4 in the left file above, and typed

dp, then the file on the right would be changed to say "program1"

as well. If we had typed do instead, then the left file

would be changed to say "program2".

For checking quickly if files are different, diff works well.

For seeing the results quickly in the terminal, sdiff is nice.

For navigating around the changes, and possibly modifying the files,

vimdiff is best.

If you have configured Git to use vimdiff, as discussed on

this page, then the command git difftool

will launch vimdiff with the differences between revisions.

Replacing in Files

We saw how we can do a search and replace operation with Vim:

:%s/old text/new text/

This same kind of substitution can be applied from the command line with the

sed command, which stands for stream editor.

If we wanted to replace "old text" with "new text" in "file.txt", we can use this command:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sed 's/old text/new text/' file.txt new text a line with nothing important here is some new text again

By default sed just prints the modified output

to the screen, it does not actually modify the file at all! If we want sed

to, we can use the -i "in place" option:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ cat file.txt old text a line with nothing important here is some old text again! ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sed -i 's/old text/new text/' file.txt ifinlay@cpsc:~$ cat file.txt new text a line with nothing important here is some new text again!

Like Vim substitutions, sed by default only does one substitution per line.

To do multiple, we can add a 'g' at the end of the command:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sed -i 's/old text/new text/g' file.txt

Using the in place option can be dangerous as a bad substitute command could wreak havoc on your files, but it is extremely powerful. If we wanted to rename a function in our project, say from "doStuff" to the more descriptive "produceReport", then we could use the following to apply the change to all files in our project:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ find . -name "*.py" -exec sed -i 's/doStuff/produceReport/g' {} \;

This uses find to find all of the Python files within the

current directory. It then uses the -exec option to pass all of

those files along to sed, which does the substitution. This kind of

thing can save a lot of time!